Hárbarðsljóð is a flyting poem from the Poetic Edda, in which Thor is challenged to battle wits with a ferryman named Harbard (Hárbarðr) for passage across an inlet. Interestingly, Harbard gets the better of the exchange, ultimately denying Thor passage and sending him around the bay on land. By which we may surmise that Harbard is not a simple mortal to have bested a god in a flyting and confidently sent him away.

In fact, it is something of a trope within Old Norse/Icelandic mythological and legendary literature for gods to travel the world in disguise. There are possibly two figures within the Norse pantheon best known for this trick. Loki, variously appearing as a salmon, a mare and, possibly, an old woman, also noted for disguising himself and Thor as a bridesmaid and bride (respectively) in the famous wedding-feast sequence from Þrymskviða. Loki certainly has form for embarrassing Thor and, of all the gods, he is the most noted for flyting, courtesy of his exchange with the gods Asgard after gate-crashing a feast in Lokasenna. (Both Þrymskviða and Lokasenna also form part of the collection known as the Poetic Edda). Yet Loki’s disguises almost invariably involve shape-shifting. The old ferryman is far more in line with the trope of the Odinic wanderer – Odin-as-vagabond, wandering the worlds of Norse mythology and meddling. And, among his varied roles, Odin does perform as the god of (good) poetry. Cases have been made for Harbard being either of these gods in disguise, and that is what I intend to look at today – the elements of the poem that correlate with other representations of Odin and Loki and thus point to Harbard’s true identity. (Spoiler – it’s Odin).

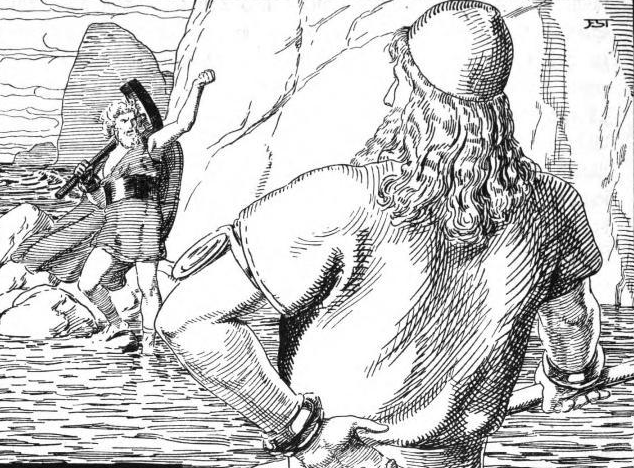

Thor and Harbard discourse over the inlet, Franz Stassen, from Die Edda:

Germanische Götter- und Heldensagen, Hans von Wolzogen, Leipzig, 1875 [1920].

But first, I suspect you have some questions such as: ‘What is a flyting poem?’ and, ‘What is the Poetic Edda?’ Our readers have varied grounding in Old Norse literary studies, so some of you will know the answer to these questions, yet as this is the first time I have written on either topic for the blog, I will first provide this context. I am, however, going to assume a certain level of knowledge regarding Thor, Odin, and Loki – my primary focus here is on the literature and the history of the literature and, while Norse Paganism is an abiding interest, I want us to keep our attention on the narrative and structure of Hárbarðsljóð.

The Poetic Edda

There are two works generally referred to as Edda. The first, usually known as either the Prose Edda or the Younger Edda is attributed to a single author – Snorri Sturluson. Snorri’s Edda is an early 13th century work comprised of four books and, despite being referred to as the Prose Edda, contains a great deal of verse and even didactic material relating to the composition of poetry. This Edda covers a great deal or Norse mythology and cosmology and preserves a great deal of what we know about Norse Paganism and, though Snorri can be accused of Christianisation and euhemerism, we owe him a great debt of gratitude.

What we are interested in though is the Poetic Edda – an anonymous collection of poems in Old Norse pertaining to mythological and legendary material. Primarily contained in a volume known as the Codex Regius (Árni Magnússon – GKS 2365 4to), the Poetic Edda has something of a confusing life. Firstly, nothing is known of the manuscript until 1643 when it came into the hands of Bishop Brynjólfur Sveinsson who, in line with contemporary thought, decided that this volume represented the source material for Snorri’s Edda. It was at this time given an erroneous authorial attribution and understood to be a coherent single work. This notion was perhaps understandable as the Codex Regius contained the full texts of a number of poems cited or only partially quoted by Snorri. In reality, it is rather more complicated than that. The Codex Regius was, in fact, compiled in the late 13th c., around fifty years after Snorri authored his Edda. Further, considering the corpus of eddaic poetry as a whole, in some instances the fragmentary quotations within Snorri’s Edda are our the earliest extant recording. However, for clarity’s sake, let’s now ignore Snorri entirely.

What we have in the Poetic Edda is a collection of poems that were composed in various periods and, unsurprisingly given its interest in pre-Christian religion, many of them likely predate the Christianisation of Scandinavia in composition. While the majority of these, as noted, are found in the 13th c. Codex Regius, some poems found within modern editions of the Poetic Edda are drawn from separate manuscripts – notable among these, AM 748 I 4to, which along with the Codex contains our focus text, Hárbarðsljóð. Now, I won’t try to tie a date to Hárbarðsljóð, simply because, trying to date any of these poems is fraught with difficulty. Most authorities cannot agree on a dating methodology, no less specific dates for each individual composition – suffice it to say that Hárbarðsljóð certainly predates it’s 13th c. textual record.

Facing pages of Hárbarðsljóð in the Codex Regius – the entire of the poem is only four pages in length (GKS 2365 4to f.12v – 13r).

Flyting

Flyting should be easier to explain. The words ‘Old Norse poetry-slam’ come to mind, but that would be deeply unprofessional, so let’s go for something else.

Flyting is in fact far from unique to Old Norse or Scandinavian cultures and can be found in Old English and Irish literature, through to high-medieval tales, Shakespeare and, one could argue, into modern poetry and rap ‘battles.’ At its most basic level, flyting is an exchange of verse insults, with those insults normally designed to attach themselves to rumour and innuendo, thereby questioning the recipient’s ability to function as a normative member of society. Essentially, that means things such as parentage, sexual-normativity, personal bravery, largesse and other intangibles would be called into question. Such accusations could be particularly damaging in medieval society where proof to counter such slander was not easy to obtain. How does one prove instances of past bravery? Or ability to perform sexually? Or parentage? It was enough of a problem that Iceland legislated against slanderous verse, with punishment set a three years’ outlawry.

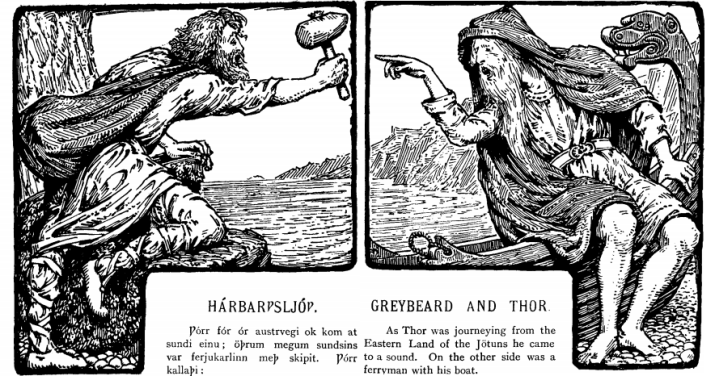

Lokasenna – Loki’s Mocking, a flyting exchange with the gods, W.G. Collingwood, from The Elder or Poetic Edda (trans. Olive Bray), London: Viking Society, 1908.

There are some superb examples of Old Norse flyting, with particularly fine exchanges found in Lokasenna – which I have already mentioned, the Icelandic family saga Bandamanna saga, and, of course, Hárbarðsljóð. In Hárbarðsljóð we see Harbard referring to Thor as a knave, a trouserless peasant, the god of serfs, strong but cowardly, and finishes with ‘go where the fiends will get you.’ All the while, Harbard compliments his own sexual prowess and bravery, while questioning Thor’s own. Thor certainly has the worst of the exchange, succumbing to exclamations of shock as opposed to witty retorts, but he nonetheless calls Harbard variously a peasant, a pervert, and a man-ling, ending with ‘I’ll reward you for refusing to ferry me, if we ever meet again.’

(A note that, given the sexual nature of much of the flyting, I strongly recommend the Larrington translation from the reference list. The older translations tend to self-censor).

Identifying the Ferryman

Thor was travelling from the east and he came to an inlet. On the other side of the inlet was the ferryman with his ship Thor called:

- Who is that pipsqueak who stands on that side of the inlet?

He answered:

- Who is that peasant who calls across the gulf.

And just like that, with little introduction, no attempt at civility between the two men, 60 verses of flyting have begun.

Thor faces Harbard in a flyting exchange, W.G. Collingwood, from The Elder or Poetic Edda (trans. Olive Bray), London: Viking Society, 1908.

We have already established that Harbard is unlikely to have been a mere mortal, yet he is unrecognised by Thor. So is he a god in disguise, or something else? While there are other creatures that resemble people and the Æsir gods in Norse mythology, such as the Vanir (gods), the Jötnar (giants), and the varied elves and dwarves, this is not one of those. The figure on the other side of the inlet is deeply intimate with Thor’s doings – indeed, so much so that Harbard frequently references events for which we have no other record. While the deeds that Harbard claims to himself are at the very least the deeds of a legendary hero if not the deeds of a god. Here we see a combination of common tropes within the literature – the god in disguise, and Thor’s inability to adapt to other’s subterfuge.

Now, it is not difficult to see why some commentators thought that Harbard was the trickster God Loki. Not only does Lokasenna represent the best-known example of flyting in Norse literature, but there are some distinct parallels between what Loki says to Thor in Asgard, and what Harbard says to Thor at the inlet. In verse 48, Harbard says:

Sif has a lover at home, he’s the one you want to meet,

then you’d have that trial of strength which you deserve.

This is a reasonably standard bit of insult verse – Harbard is accusing Sif, Thor’s wife of infidelity and naming Thor a cuckold. Nowhere else in the Old Norse corpus is Sif recorded as being unfaithful to Thor, except in verse 54 of Lokasenna where Loki says to Sif:

I alone know, as I think I do know,

your lover besides Thor,

and that was the wicked Loki.

So here Loki is stating that he alone knows who Sif’s lover is, and that is himself. Yet to identify Loki with Harbard on this logic, we must assume that the events of Lokasenna take place after the meeting in Hárbarðsljóð. The flyting in Lokasenna takes place before a gathering of the gods and thus the accusation exposes the secret, the rumour thus becoming a tool for any who wish to denigrate Thor. Moreover, Harbard’s verse implies that the lover is someone other than Harbard himself.

What else may speak to Loki as Harbard? Well there is the reference in verse 26 to Thor and Loki’s journey to Útgarðr in Jötunheimr. One of the more famous tales of Norse mythology, the gods and their companions are terrorised by Skrýmir, a giant so large that the group sleep the night in Skrýmir’s glove, thinking it a building:

Thor has quite enough strength, and no guts;

in fear and cowardice you were stuffed in a glove,

and you didn’t then seem like Thor;

you dared in your terror neither

to sneeze nor fart in case Skrýmir might hear.

Likewise, in verse 60 of Lokasenna, we have Loki telling Thor:

Your journeys in the east you should never brag of before men,

since in the thumb of a glove you crouched cowering, you hero!

And that was hardly like Thor.

This is certainly open to the same accusation as that previously quoted. Loki was with Thor in the glove, thus he is able to claim a unique position as an eye-witness, making the accusation difficult to counter. As Loki reveals the secret of Thor’s cowardice in front of all the gods, it becomes available for all to use who wish to taunt Thor. Though it should be noted that we do have full accounts of the Útgarða-Loki narrative, and in these Thor is represented as uniquely courageous – the only one of the group not fearing the rumblings of the giant.

Skrýmir and his glove, with Thor poised to attack, by Friedrich Wilhelm Heine (1882)

There are various other reasons that Harbard has been identified with Loki. A number of other lines like those above hold clear similarities between the flyting of Harbard and Loki; the detailed knowledge of the deeds and misdeeds of other deities is very characteristic of Loki; so too is the apparent willingness to twist those deeds to mock and embarrass. Yet this is an argument that has not stood the test of time, and I must give a quick reminder that we are dealing with a literary corpus. The similarity between the verses quoted above speaks to inter-textual borrowing and may owe as much to a laziness in composition as a genuine attempt by the composer to create an inter-woven narrative in which Loki and Harbard are the same person, or in which Harbard is making use of the rumours spread by Loki in Lokasenna. We don’t often like to accuse medieval authors or the development of oral narrative of laziness though, so let’s stick to ‘inter-textual borrowing.’ Yet it is not unusual nor extraordinary within medieval texts to find similar sentiments and similar lines delivered by different characters. Indeed, with a tradition such as eddaic poetry in which the verse narrative had a period of significant oral development before being committed to the page, it is reasonably common to find that while independent narratives have evolved, famous or well-known verses may remain intact with them.

Harbard is, in fact, Odin in disguise. While a simple comparison of like-verses may point to Loki, the deeper implications of the allusions within the verse point clearly to Odin. There are many indications as to who we are dealing with: in verse 16 Harbard is a war-god wreaking slaughter, in verse 18 a cunning seductor, but let’s look briefly at verses 20 and 24 as most representative of Odin.

Mighty love-spells I used on the witches,

those whom I seduced from their men;

a bold giant I think Hlebard was

he gave me a magic staff,

and I bewitched him out of his wits.

Loki may be a trickster with powers to wreak havoc, but Odin has more tangible powers as the god of sorcery and knowledge. Both elements of this verse are far more representative of Odin than Loki: the use of magic to gain advantage, and the use of cunning to gain power and knowledge. Within the corpus of Old Norse literature, Odin does not shy away from using magic to his own ends, even to seduction and rape as seen in the particularly dark tale of Rindr (told in full in the Gesta Danorum, but only alluded to elsewhere). Odin is similarly morally suspect in his pursuit of knowledge; indeed, I would suggest that is one of his defining characteristics within the mythology. Odin favours the acquisition of knowledge by means of craft and guile and gives little consideration for those who lose in such exchanges. Thor’s response to this verse is representative of how markedly he differs from his father: with an evil mind you repaid him for his good gifts. Odin/Harbard replies by saying each is for himself in such matters.

This is not, however, the most definitive example of the differences between Odin and his son as god-figures within Hárbarðsljóð, that comes in verse 24:

I was in Valland, and I waged war,

I incited the princes to never make peace;

Odin has the nobles who fall in battle,

And Thor has the breed of serfs.

In the first half of that verse we once more see Harbard as a war-god, inciting battle and pitting princes against one another. These men will die in the battles Harbard (let’s just call him Odin at this point) instigates and perpetuates, and dying in battle they will be called to feast with Odin in Valhalla until Ragnarok. The second half of that verse is perhaps the most interesting as it is almost a summation of the characters of the two gods as displayed throughout the flyting. Thor lacks subtly – he provides simple responses and fails to recognise allusion or even recognise his father, though he is in his usual ‘disguise.’ Thor is thus portrayed as simple and straight forward, and assigned to him are the simple-folk – the serfs. Odin in contrast is portrayed as witty, powerful, and morally ambiguous, and assigned to him are the nobles. Undoubtedly Odin intends these lines as an insult. By referring to only a noble class and a slave class, he places himself among the nobles and Thor among the slaves. However, if we take the hyperbole out of Odin’s delivery and imagine that his cult primarily comprised of the noble and warrior classes, while Thor’s cult was most popular among farmers, labourers and common classes, this does match our archaeological and literary evidence for the cults of both gods. In this verse more than any other does the Hárbarðsljóð author most clearly allude to Harbard being Odin.

Ultimately, however, Harbard’s name reveals all. Hárbarðr means grey-beard and, identifying his various cognomens in the poem Grimnismál, also found in the Poetic Edda, Odin finishes verse 49 with the line Gǫndlir oc Hárbarðr með goðom: [they called me] Gondlir and Harbard among the gods. It is apt. As he says near the opening of Hárbarðsljóð: I am called Harbard, I seldom conceal my name. It is Odin, the grey-bearded wanderer, calling himself Grey-Beard, who sits across the inlet taunting his son. Why I could not tell you. Odin does not always need a reason to meddle. Was it a test? Was it just for fun? Was it a punishment? I’ll leave that to your own speculation.

-Matt Firth

References:

- Feature image: Thor faces Harbard in a flyting exchange, W.G. Collingwood, from The Elder or Poetic Edda (trans. Olive Bray), London: Viking Society, 1908.

- Olive Bray, ed. and trans., The Elder or Poetic Edda, London: Viking Society, 1908. [Bilingual]

- Carolyne Larrington, trans., The Poetic Edda, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. [Translations drawn from this text]

- Jónas Kristjánsson, Eddas and Sagas, translated by Peter Foote, Reykjavík: Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag, 2007.

- Rory McTurk, ed., A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature, Oxford: Blackwell, 2005.

- Gustav Neckel, ed., Edda: Die Lieder des Codex Regius, 1983 – Titus online version [Old Norse-Icelandic]

- Margaret Clunies Ross, A History of Old Norse Poetry and Poetics, Cambridge: Brewer, 2005.

- Benjamin Thorpe, trans., The Poetic Edda, reprint, Lapeer: The Northvegr Foundation Press, 2004 (1907). [Translation]

If you liked this post, follow this blog and/or read the following blog posts:

Berserks, Revenants, and Ghost Seals – Surviving a Saga Christmas

Blood Eagles, Fatal Walks, and Hung Meat – Assessing Viking Torture

Kingship in the Viking Age – Icelandic Sagas, Anglo-Saxon Kings, & Warrior Poets

Monsters and the Monstrous in the Sagas – The Saga of Grettir the Strong

See our bibliographies on the Viking World and Chronicles and Editions.

Categories: History & Analysis

I really enjoyed reading your thoughts! They were well put together, and both useful and interesting to me! Thank you!

LikeLike